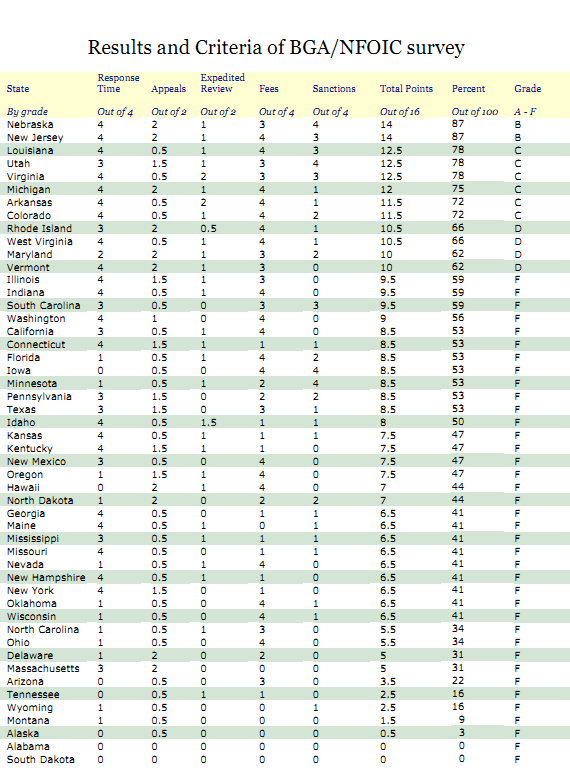

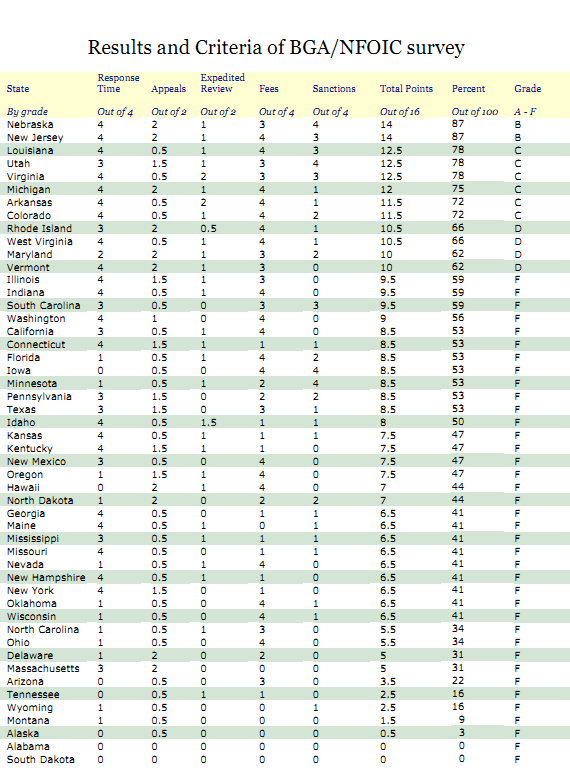

Criteria

The BGA used five criteria to assess each state. The criteria were chosen as an effort to conduct the most objective analysis of the law in each state. The procedural criteria are designed to assess the procedural guidelines in each state for obtaining public records, while the penalty criteria examine the punishment, if any, which is levied against an agency that wrongfully denies access to a public record.

The procedural criteria are as follows: (1) The amount of time a public agency or department has to respond to a citizen’s request for a public document; (2) the process a citizen must go through to appeal the decision of an agency to deny the request for the public record; and (3) whether an appeal is expedited when it reaches the court system. The penalty criteria weigh: (1) whether the complaining party, upon receiving a favorable judgment in court, is awarded attorney fees and costs; and (2) whether the agency that has wrongfully withheld a record is subject to any civil or criminal punishment.

Three of the criteria—Response Time, Attorney’s Fees & Costs and Sanction—were worth four points each. Two of the criteria—Appeals and Expedited Process—were assigned a value of two points each. Response Time, Attorney’s Fees & Costs and Sanctions were assigned a higher value because of their greater importance. They determine how fast a requestor gets an initial answer, thus starting the process for an appeal if denied, and provide the necessary deterrent element to give FOI laws meaning and vitality. Appeals and Expedited Process, although important, are not as critical in vindicating the rights of citizens and journalists who are trying to keep a close eye on government operations.

In assessing the statutes, the BGA chose not to use exemptions from disclosure as a factor in its analysis. Most state statutes contain a provision that specifically defines what records are not subject to disclosure under the act. The BGA chose not to use exemptions in weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each state’s statute because of the relative impossibility of counting each exemption. Furthermore, without a close analysis of how the exemption is interpreted judicially, it is impossible to determine the relative breadth or narrowness of an exemption. Accordingly, surveying statutes based on exemptions would be very difficult because, e.g., a state with few exemptions might exclude more records than a state with many exemptions if the first state were to interpret its exemptions very broadly and the second state were to interpret its exemptions very narrowly.

Procedural Criteria

The first three criteria that the BGA studied in assessing the strength of each state’s open records act are procedural. The three criteria involve the process the requesting party must use to gain access to public records. The BGA’s concern with these procedural requirements is that a lengthy and burdensome process is likely to discourage citizens from making requests and seeking enforcement of the statute, which will result in less disclosure of public information. Such a result would frustrate the policy of creating a better democracy through a more open government. The procedural criteria are as follows:

Response Time (4 points)

Response time is the period of time that an agency has to make an initial response to a request for a public record. A major area of concern is requests for time sensitive documents. The more time an agency has to respond to a citizen’s request, the less effective the statute becomes. For instance, statutes that provide for very long response times, or do not provide a stated response time at all, do not create any statutory assurances for a requestor, such as a journalist, who is seeking a time sensitive document. Statutes in these states may allow an agency to stall in handing over the requested materials so that they are no longer useful, or the requestor simply gives up on the request. Either result frustrates the purposes of the open records act. Thus, state statutes received more points for quicker response times. Note: The BGA only examined the time an agency has to make an initial response to a request for documents. In many states, an agency can receive an extension of time to consider a request. Our analysis did not factor in possible time extensions.

States that failed to provide for a response time received a score of 0. A state received one point if its statute simply provided that response to a request must be made within a reasonable amount of time, or language similar to that effect. This ambiguous language may lead to excessive delays in processing a request. The lack of an explicitly defined response time is of concern to the BGA. Receiving two points are states that have passed statutes requiring a response between 16 and 30 days. These states explicitly provide a response time, so that the requesting party is assured recognition of the request during a specified time period. However, 16 to 30 days is too broad of a response time. A state received three points if its statute required a response between 8 and 15 days. Four points were awarded if a state’s statute required a response between 1 to 7 days.

Appeals (2 points)

The next procedural criterion used by the BGA to weigh the strength of each state’s open records act was the appeals process a citizen can go through after being denied access to a record that is covered by the statute. If citizens are able to appeal in a cost and time efficient manner, in the forum of their choice, citizens are more likely to challenge an agency’s denial. The BGA’s method of grading this criterion is based on three elements: choice, cost and time. A petitioner should be able to choose the body that hears the appeal. The appeal process should also provide for administrative remedies to control the costs and time of appealing.

States with statutes that do not provide for an appeals process received a score of 0. These states fail to inform citizens that the denial may be reviewed, and may be reversed, by a higher authority. The law must explicitly explain the appeal process in order to fully inform citizens of their rights. States, which require a citizen to appeal directly to a court of law, with no administrative remedy, receive a half point. Under these statutes, citizens are not able to choose the forum of their appeal. In addition, these states do not provide remedies that might reduce the cost of an appeal. Appealing directly to a court will assuredly be the most expensive and consume the most time. Citizens facing several years of litigation costing thousands of dollars are less likely to challenge a denial. One point was awarded to states that require petitioners to first appeal to the director of the agency that denied them access, then to an ombudsman and only then to court. By requiring a petitioner to exhaust both administrative remedies before allowing access to the court system, these states provide the petitioner no choice of forum. Furthermore, appealing to both bodies may be burdensome on the petitioner. However, these states do provide for administrative remedies that may reduce the cost of the appeal if a favorable ruling can be achieved before resorting to court. By appealing first to the agency head and then to an ombudsman, there is a chance of getting a favorable decision in a cost and time efficient manner. Statutes requiring the petitioner to appeal to a legislatively designated entity, either the head of the agency or an ombudsman or a choice of the two and then to court earned states one and a half points. These states only require the petitioner to exhaust one round of administrative remedies before entering the court system, which is less burdensome. Furthermore, by seeking some administrative remedy, there is the potential for a favorable ruling on the appeal before getting to court. Finally, the states allowing citizens to pursue the channel of appeal of their choice received two points. These states pass each prong of the BGA’s analysis. First, citizens have total control over the forum in which their appeal will be heard. Furthermore, these states provide for administrative remedies, which may result in a favorable ruling in the least expensive and time-consuming manner.

Expedited Review (2 points)

Expedited Review means that a case’s priority on a court’s docket will be put in front of other matters because of time concerns. The BGA examined each state statute to determine if a petitioner’s appeal, in a court of law, would be expedited to the front of the docket so that it would be heard immediately. The focus was on the expedited process in courts, not in administrative hearings.

Expedited Process is a procedural feature that allows petitioners to have their grievances heard in a timely manner. Without an expedited process, it may be months or years before an appeal is heard and resolved in a congested court docket. As a result, the enormous costs of a lengthy court battle may prevent a citizen from challenging a denial. Furthermore, lengthy court battles will render time sensitive documents useless. Absent an expedited process, litigation may serve as tool to stall the production of records until the records are no longer of use, or until the citizen simply gives up on the request.

States that do not provide for an expedited process in their public record statute received a score of 0. These states do not provide any mandate to avoid the inherent problems that are associated with lengthy and costly litigation. Requiring a showing of special circumstances for an appeal to be expedited scored a half point. Such a requirement puts the burden of proof on the Petitioner rather than mandating an expedited process. Requiring an appeal to be expedited and heard ‘as soon as practicable’ earned states one point. While these states address the issue of an expedited process, and seemingly recognize its importance, they provide no meaningful mandate. Because these states leave the issue of an expedited process to the judge’s discretion, an appeal still may not be heard for months. States requiring a case to be heard within 11 to 30 days after filing received one and a half points. These states explicitly mandate a time limit and provide the petitioner with assurance of a speedy appeal. States received two points if they required a case to be heard within 11-20 days

after filing.

Penalty Criteria

In the penalty category, the two criteria the BGA used to weigh the strength of each state’s public records act focus on the penalties that are levied against an agency that has been found by a court of law to violate the statute. The two penalty criteria are: (1) whether the court is required to award attorney’s fees and court costs to the prevailing requestor; and (2) what sanctions, if any, the agency may be subject to for failing to comply with the law. These criteria are designed to assess the enforceability of a public records act. Penalties and sanctions provide incentives for agencies to comply with the law as well as a deterrent for violations. Without penalties, the procedural provisions mean very little.

Attorney’s Fees & Costs (5 points)

The first penalty criterion the BGA used was whether petitioners were entitled to attorney’s fees and court costs in the event they prevail in their action. Allowing for such an award serves two purposes. First, it assures petitioners that their expenses will be covered in the event they are successful in their appeal, encouraging people to challenge an agency’s denial. Second, awarding fees and costs to the prevailing petitioner will provide a deterrent to agencies and promote compliance with the law. The BGA’s grading scale for fees and costs contains phrases that warrant explanation. The first

is the difference between ‘may’ and ‘shall.’ ‘May’ means that fees and costs are to be awarded at the judge’s discretion. ‘Shall’ means that fees and costs must be awarded to the prevailing petitioner. A statute that states fees and costs ‘shall’ be awarded will be stronger than a statute that provides fees and costs ‘may’ be awarded. The second is the difference between ‘prevail’ and ‘substantially prevail.’ ‘Prevail’ refers to a situation where the petitioner wins on all points, and is given access to all the records requested. ‘Substantially prevail’ refers to a situation where the petitioner wins on only some points, and loses on other points and the petitioner is only given access to some of the requested records. States that award fees and costs to petitioners that only substantially prevail will be stronger than those that require the petitioner to completely prevail in order to get fees and costs.

State statutes that do not provide that a prevailing petitioner could collect fees and costs received no points. These states provide little incentive for an agency to comply with the law. Furthermore, the citizens denied access to a record are less likely to appeal that denial to a court if they know that they will have to shoulder the burden of paying for the litigation. Allowing recovery of fees and costs in the event the agency acted in an arbitrary and capricious manner and/or bad faith in denying the record earned states one point. To prove either is an extremely high burden of proof, and will only be discernable in the most extreme circumstances. Thus, for a majority of cases, fees and costs will not be available to the petitioner if this standard is applied. States allowing an award of attorney fees and costs at the judge’s discretion when the petitioner prevails received two points. These states provide no assurance that the fees will be awarded; however they leave the option open. Furthermore, these states require the petitioner to win on all points before a judge will even consider awarding fees and costs. States receiving three points also leave awarding fees and costs to the discretion of the judge, however the petitioner must only substantially prevail before a judge may consider the awarding attorney fees and costs. Four points were awarded to states that require an award of fees and costs to a prevailing petitioner. These states assure petitioners from the outset

that they will have their expenses covered in the event that they win. Parties in these states are more likely to challenge a denial because they know their costs will be covered.

Sanctions (4 points)

The final criterion the BGA examined in assessing the strength of each state’s open record act was sanctions. We looked to see whether there were provisions in the statutes that levied penalties against a state employee who was found by a court to be in violation of the statute. Without a sanctions provision, a public records statute means very little. By holding out the possibility that individuals will be held accountable for undermining the statute the law is more likely to achieve compliance. States that do not specifically punish an agency for non-compliance with the statute received no points. These states lack a serious commitment to the policy underlying an open records

act. One point was awarded to states with statutes that provide for either criminal or civil sanctions in the event there is a violation of the law. These states provide some incentive for compliance. The BGA gave two points for statutes that provided for both criminal and civil sanctions. These states exhibit a heightened commitment to enforcing their laws. Receiving three points are states that provide for criminal and/or civil sanctions and increase those sanctions for multiple offenses. These states recognize the problems with continued non-compliance. Finally, states that allowed for termination of an employee who violates the statute received four points. These states provide for

the individual employee who has violated the statute to be held directly responsible for his or her wrongful conduct. While fines may be paid out of the agency budget, this provision mandates direct accountability and is most likely to result in compliance.

For more information, contact:

Jay E. Stewart

Executive Director, Better Government Association <http://bettergov.org>

Phone: (312) 427-8330; Email: info@bettergov.org

Charles N. Davis

Executive Director, National Freedom of Information Coalition <https://nfoic.org>

Phone: (573) 882-5736; Email: daviscn@missouri.edu